Rust TestingMicro-framework

Exploring rust Macros

source code: github - license: cc0

What is rust?

As a systems researcher, I really enjoy the in-development systems language rust. Over the years, we have made substantial systems progress in spite of languages and tools that have been insufficient in their analysis of forms of safety. That is, C and C++ have prevailed as systems languages even though, due to technological constraints and even social convention, they largely fail to create reliable systems without substantial manual effort to predict defects.

The rust programming language is a experimental systems language maintained by Mozilla

Rust uses known and well-researched programming language and compiler techniques to move the systems world toward stricter compile-time analysis without giving up performance nor the ability to write low-level code. For instance, rust can annotate the lifetime of variables essentially creating a contract that certain data structures can be used safely in concurrent environments. Also, rust can guarantee that certain functions will never mutate data and will always return data.

Nothing here is particularly new, but rust is the first example of a language that is being engineered for general-purpose and wide-scale systems use. Mozilla, the developers of rust and Firefox, are rewriting the innards of Firefox in rust to improve the reliability of a formerly C++ codebase well-known, as most of the software in its class, for vulnerabilities and memory-leaks. I can certainly see the majority of the core operating system being eventually written in rust, replacing much of our C (Unix, Linux, Windows) infrastructure for similar motivations.

While much of rust's power comes from the strictness of its syntax, the language designers have pained themselves to provide flexibility. Often the language can reasonably infer the intention of the code and only complain upon an ambiguity. What is more interesting, though, is the macro system which allows for the actual syntax of the language to be extended. In a testament to the power this enables, much of the syntax of rust has been deprecated and moved to imported macros.

The project I will present here makes use of rust macros to provide a DSL for behavioral testing. It does not have all of the bells and whistles of other such frameworks, but it works rather well for my purposes.

Some Code

Now, normally, we would write the tests first and watch the compiler fail, but for the sake of illustration let's start with the code we want to test first. In this case, a function that adds two floating-point values:

// math.rs

pub fn add(a: float, b: float) -> float {

a + b

}

We want to make sure that this function works for a variety of inputs. So, we can write a series of tests that describe what this function should do.

Some Tests

And now for our rather contrived tests:

// math_spec.rs

// Here, I will compile math.rs above to a library.

extern mod math;

// We add the testing logic and dsl:

use tester::*;

mod tester;

// A describe block to name the module we are testing:

describe!("math", {

// A test block to name the function we are testing:

test!("add", {

// And then a list of behaviors and code that test them follow:

should!("add two positive numbers", {

must!(math::add(5.0, 5.0) eq 10.0);

})

should!("add two negative numbers", {

must!(math::add(-5.0, -5.0) eq -10.0);

})

should!("add a negative and positive number", {

must!(math::add(-5.0, 3.0) eq -2.0);

})

should!("add a positive and negative number", {

must!(math::add(5.0, -3.0) eq 2.0);

})

})

})

The must! macro is complemented by a wont! macro, which reverses the logic of the assertion. Also, there is, beyond eq which simply compares, a floating-point specific compare near that will allow a deviation of a particular amount to account for inaccuracies inherent in floating-point math. For instance, must!(math::add(3.1415, 4.1235) near 7.265 within 0.00001); will check that the result is within +/- 0.00001 of the given value. The example in the repo is more feature inclusive.

Running

To run the tests, first I compile the original code into a library (you can directly import as well by removing the extern in the test code):

rustc --lib math.rs

And then I compile the test code (using ‑L to tell rustc to look in the current directory for our math code):

rustc math_spec.rs -L .

And then run the resulting executable:

./math_spec

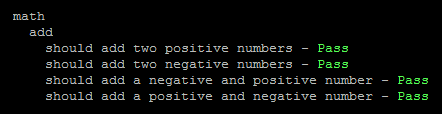

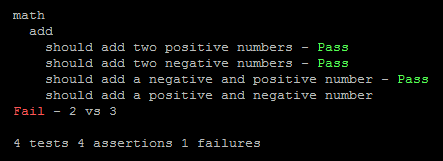

And I get:

If something were to fail, you'd see this:

A failed test shows the expected and given values.

Cool!

Macros

The syntax for the test macros is more thoroughly described at the project repository. As you can tell, it is not difficult to understand. As all behavioral testing frameworks, the code written for the blocks is easily read as an English sentence lending itself to a decent expression of what the function is meant to do without looking at the test code or implementation. Let's look, however, at rust macros in general.

The syntax describe!( ... ) says that we want to invoke the describe macro which is written within tester.rs. It is a bit complicated and hard to debug, all things considered, but it basically replaces itself within the AST with a main function containing some boilerplate code and then the code you wrote and passed into the describe block as a closure. The macros test! and should! work similarly, adding closures of the code you provide to an array to be invoked later. Here is the implementation of the test! macro:

// The implementation for the should! macro

macro_rules! should(

($prompt:expr, $func:expr) => ({

_tests.push(

Test { name: $prompt,

func: |_| -> ~[uint] {

let mut _failure = false;

let mut _successes = 0;

let mut _fails = 0;

$func;

if (!_failure) {

::std::io::print(" - ");

::std::io::println("\x1b[32;1mPass\x1b[39;0m");

}

else {

::std::io::println("");

}

~[_successes + _fails, _fails, _successes]

}

}

);

})

)

In rust, creating a macro requires that you type out (where name is the name of the macro as you'd invoke it, input is a list of tokens you expect to see and output is valid, parseable code that the macro will become):

// Creating a new macro:

macro_rules! name(

(input) => ( output )

)

In the case of should!, I have it take as inputs a expr called $prompt and a 'expr' called '$func'. The $prompt and $func are placeholders for what the programmer writes when the macro is used and expr is a type of token, which means that each of these should be expression. Notice there is a comma between them. There can be practically any unambiguous characters there and it is expected that those characters will be typed by the programmer to use the macro. I intend for $prompt to be a string containing something like "add two numbers" and the $func to be a block. They will be essentially copy/pasted in with the tokens passed to it.

I then expand the macro out to push a new struct called Test (defined elsewhere) which contains the string and a closure to an array already established (with the test! macro) of tests called _tests. The closure contains the block of test code surrounded by variables that check and respond to failure. The block returns an array reflecting how many assertions passed or failed.

The power of rust is revealed here. In fact, macros are far more involved. Here is the full documentation. When you type out should! in your code, the compiler will expand the macro and place the result in the AST. It can do this without giving up any of those nice features we talked about earlier and it can do this without stalling the compilation process. With this, you can add syntax extensions to the language without having to worry about the specification for the language becoming too bloated or stubborn.

Feature Requests

If you would like to contribute, how about adding a few things?

- Random test ordering. That'll be rather easy since tests are already in an array, they just need to be randomly iterated.

- "Let" blocks that allow easy creation of objects to reduce copy/paste.

I'll appreciate any contributions. Send a pull request through github. Thanks!

Tags

Comments

If you'd like to comment, just send me an email at wilkie@xomb.org or on either Twitter or via my Mastodon profile. I would love to hear from you! Any opinions, criticism, etc are welcome.

Donations

If you'd like to make a donation, I don't know what is best for that. Let me know.

Copyright

All content off of this domain, unless otherwise noted or linked from a different domain, is licensed as CC0